a discovery of forgotten things

I recently attended a reading by the police officer and poet, Edward Doyle-Gillespie. As a listener in the audience that evening, I allowed myself to experience the beauty, grit, and catharsis that carefully chosen words can convey. His poetry unearthed memories of forgotten places, objects, and dreams. One line in particular explored the discovery of a forgotten book which struck me as so prescient. I have been thinking about the concept of nostalgia lately and the visual language from this poem conjured up recollections of my grandmother’s house and the room in which my mom and her sisters slept.

As a child, I would explore the sun-filled, second floor room, opening the spare closet, trying on vintage coats and sheepskin gloves. The boards creaked under foot when I walked from one side of the room to the other. I would open wardrobe drawers and inhale the curiously pleasant — yet medicinal — moth ball aromas. A bureau in the corner of the room was of particular interest to me. It housed old encyclopedias, a mix of reference books and fiction, as well as a considerable collection of National Geographic volumes from the 1960s. I spent many afternoon hours flipping through the faded pages, intrigued and mesmerized by faraway lands, exotic cultures, and astonishing animal life. At night, I would curl up on one of the three rigid twin beds, tucked under heavy patchwork quilts. It was this memory that stayed with me. And it was this memory that inspired me to uncover things I had forgotten.

Serendipitously, I happened to be scrolling through Instagram the next day and came across a new post from a follower/friend. She shared a link to her “Blackout Poem in Blue” that she created a while back. That spark led to an idea that started the journey into a wonderfully creative writing exercise.

the source material

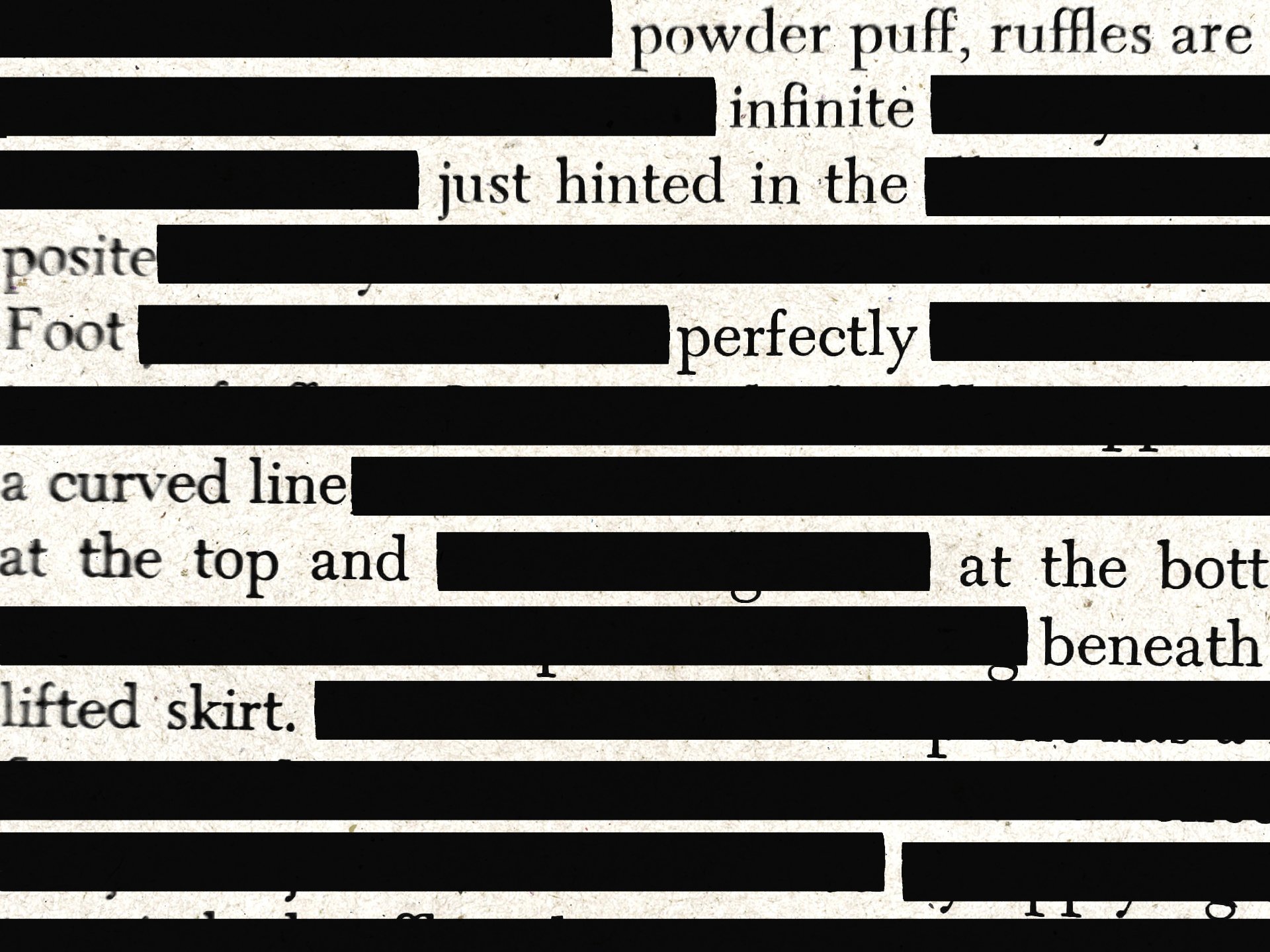

Blackout poetry, or erasure, is a form of found poetry or found object art created by erasing words from an existing text in prose or verse and framing the result on the page as a poem [Wikipedia]. The resulting text can be arranged into lines or stanzas, and the blacked out page is an artful and interesting presentation as well. The original content can be any written work — books, magazines, newspapers — and using diverse source material can result in entertaining and lively constructions.

Several years ago, I went on a hunt for vintage books. I found a handful of rare gems that offered a host of possibilities: a Hans Christian Andersen book of fairy tales from 1919; John Martin's Big Book for Young People No. 14, an illustrated children’s storybook published in 1930; and, my personal favorite, the Singer Sewing Book from 1949. The language in the sewing manual is peppered with gendered stereotypes and expectations that can easily be interpreted into expressions of desire, pleasure, and eroticism. The Singer Sewing Book went on to provide pointed quotes for my Woman's Work project which wove together the pastime of embroidery with the act of self care and masturbation. With this in mind, I chose the sewing book as a starting point for the blackout poems.

what lies beneath

Language has power. The words we choose carry weight, place intention, and imply meaning far beyond the original content on the page or on the screen. The Singer Sewing Book is a window into an era for a particular group of women: middle class, predominantly white, homemakers with free time. The expected role of women for much of the 20th century was in the home and for the service of the home. The book is positioned with this perspective.

“Perhaps the most rewarding of all hobbies for a woman is sewing. Not only is it an outlet for her creative impulse, a way to make use of her sense of design, her deft fingers, her enjoyment of color and texture, but the things she makes can beautify her home and provide for herself and her family the kind of clothing most becoming to them at a great saving over the cost of buying such items.”

Much like the nature of Woman’s Work, the words that revealed themselves in my blackout poem exercise were intimate and wistful.

“The powder and lipstick

You try in front of your mirror.

You hope when you are fearful

that a visitor or your husband,

Will not look, together.

Therefore,

you are free to enjoy

every part of you.””

The words when framed in their consecutive order took on new meaning and exposed a subtext of longing, isolation, and resignation. It is a picture of a woman’s confinement to her place in the world, seeking rare private moments to herself, before her kids got home from school, before her husband returned from work, before dinner had to be prepared, and household chores needed attending to. The best this prototypical woman could hope for was her time to sew. And even in that, she is fulfilling an obligation to her household as a productive worker, not an individual with dreams and aspirations. Sewing kept her hands and mind busy in a manner that was acceptable to the established order.

“Never approach sewing with a sigh or lackadaisically. Good results are difficult when indifference predominates.”

beyond the poems

As a writer, the Blackout Poems are a helpful exercise to create a tangible work product when I am at a loss for words, not feeling inspired, and looking for a place to begin. As an artist, the use of language from the source material form a vivid portrait of an era steeped in nostalgia that was, at best, questionable when it came to empowering women. As a woman, exposing truths and unmasking realities that are buried beneath the surface of the content was my objective with the Blackout Poems. The results were oddly satisfying.